Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR

Online!

Feb. 14 show

Victorian mourning and the Lincoln funeral train

|

The spring will mark the 150th anniversary of the funeral that became the largest in the country's history until then - and the Abraham Lincoln funeral train came through the Hoosier state.

Hoosier History Live will pay tribute to the anniversary with a show about the Lincoln funeral cortege - the assassinated president's body lay in state at the Indiana State Capitol in April 1865 - as well as Victorian-era mourning customs.

Hoosier History Live will pay tribute to the anniversary with a show about the Lincoln funeral cortege - the assassinated president's body lay in state at the Indiana State Capitol in April 1865 - as well as Victorian-era mourning customs.

Artifacts related to Victorian mourning are included in an exhibit that opened this month at the Indiana State Museum titled "So Costly a Sacrifice: Lincoln and Loss." The exhibit features dozens of artifacts related to the Civil War and Lincoln, including a Confederate artillery shell that hit troops commanded by Col. Eli Lilly and the last portrait painted of Lincoln (1807-1865) from life.

Artifacts related to Victorian mourning are included in an exhibit that opened this month at the Indiana State Museum titled "So Costly a Sacrifice: Lincoln and Loss." The exhibit features dozens of artifacts related to the Civil War and Lincoln, including a Confederate artillery shell that hit troops commanded by Col. Eli Lilly and the last portrait painted of Lincoln (1807-1865) from life.

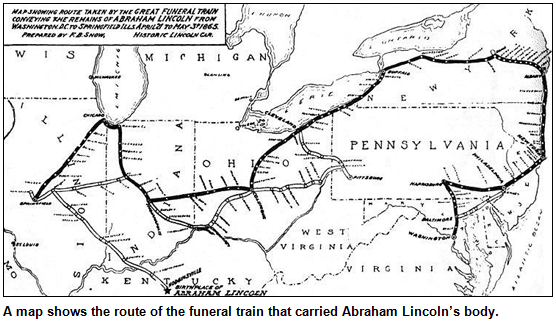

En route on a 20-day journey from Washington D.C. to Springfield, Ill., the Lincoln funeral train had three significant stops in the Hoosier state:

- Richmond, where church bells rang simultaneously and Gov. Oliver P. Morton boarded the train.

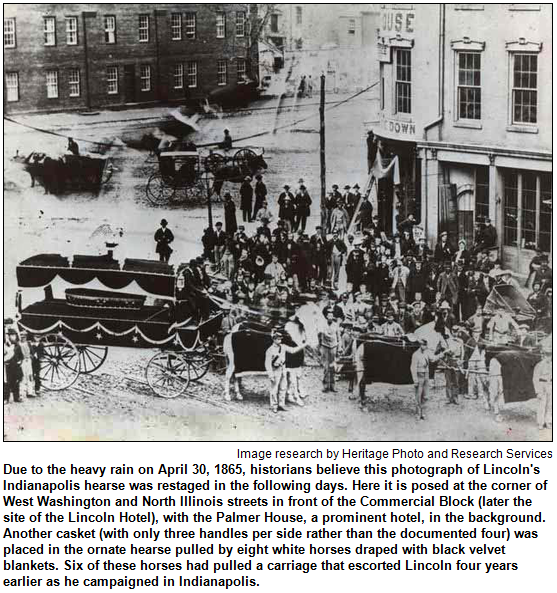

- Indianapolis, where despite a rainfall so heavy it was described as "torrential," a crowd of Hoosiers estimated as high as 50,000 - more than the entire population of the Hoosier capital then - paid respects at the Statehouse rotunda.

- And Michigan City, where problems on the railroad tracks necessitated an unplanned stop as the train was bound for Chicago. As at other stops, a funeral service - an impromptu one, in this case - was held for Lincoln.

Our previous shows about Abraham Lincoln have focused on earlier eras because the 16th president spent so much of his young life - from ages 7 to 21 - as a Hoosier.

Guests on a show last February about young Abe's relationships with his parents included Dale Ogden, chief curator of cultural history at the State Museum. Dale, an expert on Lincoln's years in Indiana, will join Nelson in studio for this show as well.

Guests on a show last February about young Abe's relationships with his parents included Dale Ogden, chief curator of cultural history at the State Museum. Dale, an expert on Lincoln's years in Indiana, will join Nelson in studio for this show as well.

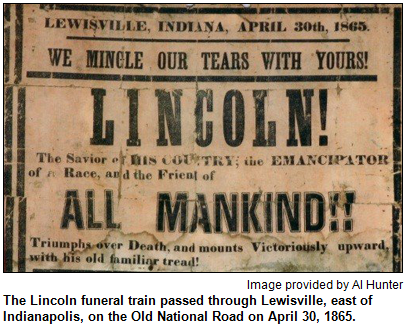

Another guest will be Al Hunter, a history columnist for The Weekly View, a community newspaper that serves the Eastside of Indy. Al has written two books about the historic National Road in Indiana. He has been working on a book about the entire journey of the Lincoln funeral train, with a particular focus on the trip's final portion from western Ohio, across Indiana, and to its final destination.

According to Al, so many people dropped buttons, keys and other personal remembrances into the open casket at each stop that the president's coffin continually had to be "swept," or cleaned of memorabilia.

According to Al, so many people dropped buttons, keys and other personal remembrances into the open casket at each stop that the president's coffin continually had to be "swept," or cleaned of memorabilia.

Because Lincoln was shot on Good Friday (and died the next day), his passing during Easter weekend "became almost a religious experience" for residents of Northern states like Indiana, Dale Ogden says.

He notes that, because the telegraph was a relatively new invention in 1865, the assassination also became "the first national event the country experienced simultaneously." In earlier eras, news traveled slowly by letter or word of mouth.

During our show, Dale also will share insights about the approach to death and mourning during the Victorian era. Most funerals were held at home in a greeting room (hence, the origin of the term "funeral parlor"); socio-economic classes handled mourning in different ways.

The state museum's exhibit includes the funeral wardrobe of a family from Corydon, as well as a child's coffin, circa 1870, from Noble County. The average life expectancy during the era was 45 years old, a statistic skewed by so many deaths of children and infants.

During our show, Dale will talk about what has been called the "unprecedented carnage" of the Civil War. By the end of the war, more than 25,000 Hoosiers had been killed in battle or died of diseases that quickly spread in the soldiers' camps.

"The carnage of the Civil War is almost impossible to overstate," Dale Ogden says.

"The carnage of the Civil War is almost impossible to overstate," Dale Ogden says.

With Lincoln's death soon after the war ended, the president also, Dale notes, was regarded as a "martyr." To enable as many Americans as possible to pay their respects, the funeral train took a circuitous route from Washington, D.C.

In the eastern half of Indiana, the funeral train ran on tracks that nearly paralleled the Old National Road. So, in addition to Richmond, the train passed through Centerville, Cambridge City and other towns before stopping in Indianapolis, where the slain president's coffin was transferred to a hearse drawn by four white horses. Led by Gov. Morton, a procession formed to accompany the hearse to the Statehouse.

According to our guest Al Hunter, mourners included residents of Philadelphia and dozens of other cities who flocked to Indianapolis because their hometowns were not on the train's route. The heavy rainfall meant that some outdoor events - including a speech by Gov. Morton, a fierce ally of Lincoln and supporter of the Union cause - were canceled or shifted indoors.

On April 30, 1865, public viewing at the Indiana State Capitol began at 8 a.m. It continued until 10 p.m.

Learn more:

|

Roadtrip: Pogue's Run in Indianapolis

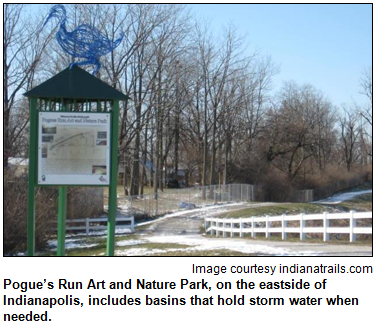

Guest Roadtripper Jim Lingenfelter of Five2Five Design Studio suggests we explore the stream Pogue's Run, which he describes as "a dubious historic remnant that flows through several historic neighborhoods and ends underground through downtown and into the White River."

Pogue's Run has been called a source of pestilence, a major pathway for early settlers, an impediment to growth of the city and a location for two major urban art installations.

Starting near Brightwood on the near east side, Pogue's Run flows through Brookside and Spades Parks, Windsor Park and Cottage Home neighborhoods, Tech High School and the Legacy Center before going underground near the Holy Cross neighborhood.

Starting near Brightwood on the near east side, Pogue's Run flows through Brookside and Spades Parks, Windsor Park and Cottage Home neighborhoods, Tech High School and the Legacy Center before going underground near the Holy Cross neighborhood.

Prior to the arrival of early white settlers George Pogue and John Wesley McCormick, Indians and wildlife would often follow Pogue's Run as a pathway. Pogue (c.1763-1821) was a blacksmith from Connersville, Ind., and in 1819 he blazed a trail that corresponds with the present-day Brookville Road. The creek became known as Pogue's Run after Pogue mysteriously disappeared from Indianapolis in April 1821; his body was never found.

When Indianapolis was laid out, only Pogue's Run running diagonally across the southeast portion of the "Mile Square" disturbed the orderliness of the grid pattern. Alexander Ralston had to make compromises due to the stream's location within the congressional donation lands given for the future Indianapolis. Before the state government could be moved to Indianapolis from Corydon, $50 was spent to rid swampy Pogue's Run of the mosquitoes that made it a "source of pestilence."

In the so-called Battle of Pogue's Run on May 20, 1863, during the American Civil War, several Democrats leaving the state party convention on the railroad running parallel to Pogue's Run threw various firearms and knives into the creek because Union troops were looking for contraband weapons. Two decades later, in 1882, the Run flooded, killing at least ten people.

The Pogue's Run Art & Nature Park can be seen south of I-70 on the east side of Indianapolis; it's a 43-acre refuge for wildlife and art. Best to get off the interstate and just go explore the trails!

History Mystery

Abraham Lincoln was the first person to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse. The second person, a Hoosier who achieved national fame, died in 1916. According to several accounts, more than 35,000 people filed past his casket at the Statehouse.

Question: Who was the famous Hoosier?

The call-in number is (317) 788-3314, and please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air. Please also do not call in to the show if you have won any prize from WICR in the last two months.

The prize pack is a pair of tickets to the Indiana Repertory Theatre and two passes to the President Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site, courtesy of Visit Indy.

Your Hoosier History Live! team,

Nelson Price, host and

creative director

Molly Head, producer, (317)

927-9101

Richard Sullivan, webmaster

and tech director

Pam Fraizer, graphic

designer

Garry Chilluffo, media+development director

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support: Indiana Authors Award | Indiana Historical Society | Lucas Oil | Santorini Greek Kitchen | Society of Indiana Pioneers | Story Inn

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Our ever-expanding archive

Underwriters make more Hoosier History Live podcasts available for listening

Thanks to the Riley Old Home Society for sponsoring the podcast of James Whitcomb Riley: before he was famous. Hoosier History Live also thanks Bonnie and Jim Carter for sponsoring Historic women's groups, which they dedicated to the memory of longtime Indianapolis Woman's Club members Eunice Roper Carter and Leah Porter Carter, and for sponsoring World War I and Indiana, which they dedicated to the honor of Fred N. Ropkey.

You can hear these podcasts on the upper-left column of our home page on our website, and also on our "Listen" page.

Feb. 21 show

Civil War and African Americans in Indiana

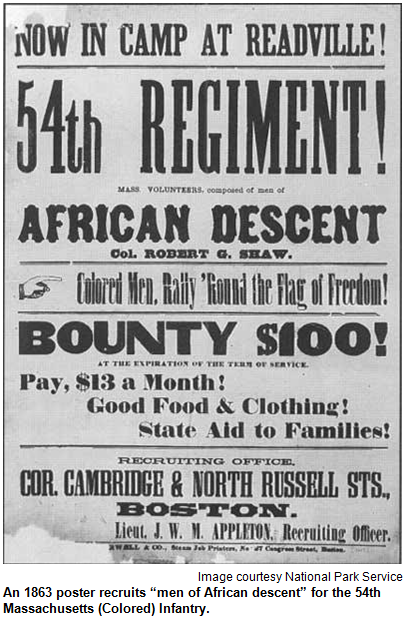

During the final years of the Civil War, African Americans from Indiana fought in a regiment called the 28th U.S. Colored Troops. Earlier during the war - before that regiment was organized - blacks from Indiana joined fighting units from other states, including a legendary infantry from Massachusetts depicted in the movie Glory (1989).

As Hoosier History Live salutes Black History Month, we will explore a range of aspects related to the Civil War, including life for African-American families who remained on the home front in Indiana.  In Putnam County, a black man who enlisted in the 28th Regiment may have been intentionally poisoned before he could serve in combat, according to research by one of our guests.

In Putnam County, a black man who enlisted in the 28th Regiment may have been intentionally poisoned before he could serve in combat, according to research by one of our guests.

Nicole Etcheson, a Ball State University history professor, became intrigued by the life of Robert Townsend, who may have purchased a poisoned pie when the 28th Regiment was being mustered in Indianapolis. Nicole says she researched Townsend after discovering he was the only African American in Putnam County with a tombstone from the 1800s.

In addition to Nicole, Nelson will be joined in studio by historic preservationist Maxine Brown of Corydon. As she reported in a Roadtrip during a show last month, Maxine has been coordinating the renovation of a historic house built by a Civil War veteran wounded in the Battle of Petersburg, also known as the Battle of Crater.

The veteran, Leonard Carter (1845-1905), was born in Floyd's Knobs, but he settled in Corydon with his wife after the war. The small bungalow that he built for his family - known as the Carter House - was built circa 1891.

According to some accounts, more than 1,500 black men from Indiana fought in the Civil War. That happened even though the 28th Regiment wasn't formed until 1864 because some Hoosiers persisted with objections to black soldiers.

Earlier in the war, African Americans who wanted to fight for the Union cause had to enlist in other state's regiments, including the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Glory, the movie starring Denzel Washington that focused on that unit, won three Academy Awards.

According to our guest Nicole Etcheson, several reports during the Civil War described the sales of poisoned food to black troops. Robert Townsend, who lived near Putnamville, had purchased a pie from a peddler before falling violently ill and eventually passing away in 1865. His pension records link the illness to the pie, Nicole says.

She is the author of A Generation at War: The Civil War in a Northern Community (University of Kansas Press, 2011).

Our guest Maxine Brown has won praise for her preservation work with African-American landmarks in southern Indiana. They include the Leora Brown School, a cultural center housed in a restored school - once known as the Corydon Colored School - where, before desegregation, generations of African-American children were educated.

© 2015 Hoosier History Live! All rights reserved.

Hoosier History Live!

P.O. Box 44393

Indianapolis, IN 46244

(317) 927-9101