Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR

Online!

Oct. 31 show

Race relations in 1950s Indy: rare perspectives

|

While growing up in Indianapolis during the 1950s, one of our guests, a white youth, attended Shortridge High School and lived near Woodstock Country Club. But Dwight Ritter spent much of his time in black neighborhoods, befriending peers who went to Attucks High School.

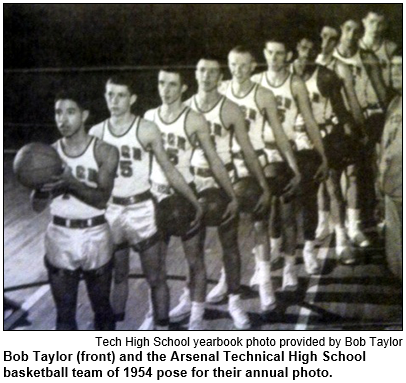

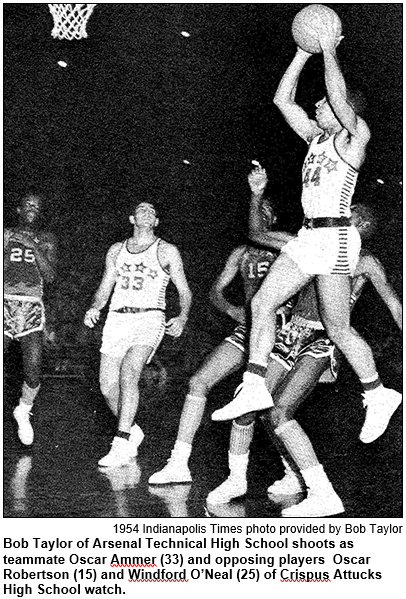

Our other guest grew up on the near-eastside and, in fall 1951, was among the small group of African-American students who attended Tech High School in the second year that school's student body was integrated. Bob Taylor became an outstanding basketball player at Tech but befriended - even though he played hoops against - many of the players on the legendary Attucks teams that won back-to-back state championships.

Our other guest grew up on the near-eastside and, in fall 1951, was among the small group of African-American students who attended Tech High School in the second year that school's student body was integrated. Bob Taylor became an outstanding basketball player at Tech but befriended - even though he played hoops against - many of the players on the legendary Attucks teams that won back-to-back state championships.

To share insights from their unusual perspectives of interacting extensively with the opposite race during an era in which much of the Hoosier capital was segregated, Dwight, now 74, and Bob, 78, will be Nelson's studio guests.

Dwight, who eventually attended what was then the John Herron Art Institute, as well as Indiana University, became a writer, graphic designer and lyricist based in Cape Cod. He is returning to his hometown in connection with the publication of his coming-of-age novel, Growin' Up White (Iron Press), which describes Indy as a "hotbed of bigotry" during the 1950s.

After graduating from Tech in the Class of '54 (which, with 740 students, was less than 5 percent black then), our guest Bob Taylor earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Purdue. He went on to a distinguished career as an engineer in the aerospace industry, followed by a 20-year career at Eli Lilly and Co. In 1990, he became the first African-American trustee at Purdue.

Growin' Up White describes several clashes between whites and blacks, ranging from the casual use of racial slurs to violent episodes in which popular students at Shortridge harassed black peers from Attucks. Although Dwight changed the names of most people and fictionalized some settings in his novel, he says many of the episodes are derived from incidents that occurred during his boyhood.

Names of several city landmarks and institutions - from Shortridge and Attucks to the long-gone Fox Burlesque Theater, the Golden Hill neighborhood and the former WFBM Radio - are sprinkled throughout the novel.

Names of several city landmarks and institutions - from Shortridge and Attucks to the long-gone Fox Burlesque Theater, the Golden Hill neighborhood and the former WFBM Radio - are sprinkled throughout the novel.

Like the book's protagonist, Dwight says he spent much time as a child and teen in black neighborhoods for several reasons.

His father was a doctor and civil rights activist who often came to the aid of black residents, including some injured in assaults by whites. And because his mother also worked (a classically trained pianist, she enjoyed a thriving career as a performer and teacher), young Dwight often was entrusted to the care of the family's African-American housekeeper. In her neighborhood, he developed friendships with black children and teens.

"I tried to 'hide' those friendships from my classmates at Shortridge," Dwight says. "Frankly, most of my Shortridge friends were racist."

"I tried to 'hide' those friendships from my classmates at Shortridge," Dwight says. "Frankly, most of my Shortridge friends were racist."

Our guest Bob Taylor attended an all-black elementary school because, he notes, in the 1940s Indianapolis Public Schools grade schools were not yet integrated. Even so, he interacted as a child with white peers because his family's home was in a "borderline" neighborhood near Brookside Park, where children of both races played - although, in Bob's recollection, seldom together.

His oldest siblings attended Attucks, but Bob says he was given the choice of enrolling there or at Tech; he opted for the latter in part because of its proximity to his home.

His oldest siblings attended Attucks, but Bob says he was given the choice of enrolling there or at Tech; he opted for the latter in part because of its proximity to his home.

"For those of us who were basketball players, the (racial tension) wasn't too bad," he says. "We were excluded from the social life at Tech, which is why we went to parties with friends from Attucks and Shortridge."

The Tigers basketball teams at Attucks, led by future NBA star and Olympic gold medalist Oscar Robertson, became the first from an African-American high school in the country to win a state championship in any sport when they captured successive titles in 1955 and '56.

But Bob Taylor's team at Tech won the city championship in 1954, beating Attucks - even though several of the future state champion players were on that year's Attucks team.

Growin' Up White describes the range of reactions in Indy's white community to the ascendency of the Attucks teams.

Much of the novel, though, unfolds earlier in the 1950s, when the main character ages from 11 to 13; he poses disciplinary problems, which author Dwight Ritter says is a reflection of his own adolescence. His rebellious nature was another reason his parents entrusted much of his care to their beloved housekeeper, a strict disciplinarian.

After graduating from IU and marrying, Dwight left Indiana in 1964. As a lyricist, he has written music for the Sesame Street TV series; as a graphic designer and artist, he has done a vast range of work. He also produced and directed the PBS documentary Being Amish.

During his return visit to his hometown, Dwight has been teaching art to youth at Christamore House on the near-westside. After our show, he will sign copies of Growin' Up White at Bookmamas in Irvington; his signing will begin at 2 p.m. Saturday.

Learn more:

Roadtrip - You are There 1816: Indiana Joins the Nation

|

Guest Roadtripper Rachel Hill Panko, director of public relations at the Indiana Historical Society, recommends a visit to You Are There 1816: Indiana Joins the Nation at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center in downtown Indianapolis.

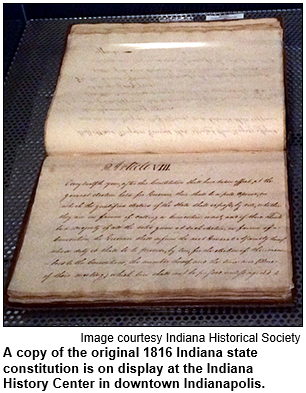

Visitors are able to step through an image of the cover of the Indiana Historical Society's copy of the 1816 Indiana State Constitution projected on a very fine screen of mist. From there, visitors enter a room in Corydon where debates have been taking place between Hoosier delegates to the Constitutional Convention, and actors pull visitors into the conversation.

Discussion topics include the requirement of all young, able-bodied men to serve in a state militia, the creation of a state-supported system of education and the prohibition of establishment of private banks. The handwritten IHS copy of the original 1816 Constitution also is on display as you enter the exhibit.

Your Hoosier History Live! team,

Nelson Price, host and

creative director

Molly Head, producer, (317)

927-9101

Richard Sullivan, webmaster

and tech director

Pam Fraizer, graphic

designer

Garry Chilluffo, media+development director

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support: Indiana Historical Society | Lewis Kappes Attorneys at Law | Lucas Oil | ShowCase Realty | Story Inn

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Nov. 7 show - encore presentation

Epidemics in Indiana history

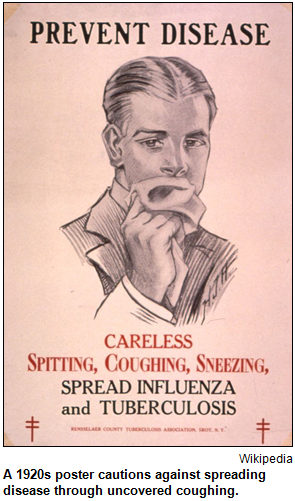

Flu season is upon us, and the Ebola panic of last year certainly hasn't been forgotten. So Hoosier History Live will explore epidemics in Indiana's past.

Flu season is upon us, and the Ebola panic of last year certainly hasn't been forgotten. So Hoosier History Live will explore epidemics in Indiana's past.

Did you know a malaria epidemic swept Indianapolis just as the Hoosier capital was getting under way in the 1820s? Some doctors blamed the epidemic on the swamps and marshland that were on the new city's site, chosen because of its central location.

The impact of that early epidemic, plus others that affected Indiana, is the focus of this encore broadcast (original air date: Nov. 15, 2014) featuring two Indianapolis-based medical historians as Nelson's studio guests.

The influenza epidemic of 1918, a cholera epidemic of the mid-1800s, the polio scare that prevailed for most of the first half of the 20th century and the AIDS epidemic that caused panic during the 1980s and '90s are among the crises explored during the show.

Nelson and his guests also explore the devastating impact of tuberculosis during the late 1800s and early 1900s - even though "epidemic" may not be the most accurate term to describe the widespread TB cases. (Tune in to the show for an explanation.)

Our studio guests are:

- Dr. William McNiece, president of the Marion County Historical Society. Dr. McNiece is an anesthesiologist at IU Health's Riley Hospital for Children.

- Bill Beck, an author and historian who has written dozens of business and institutional history books, including histories of Indiana hospitals. The founder of Lakeside Writers' Group, he is treasurer of the Marion County Historical Society.

During the show, our guests share insights about the panic over potential epidemics, including a swine flu scare in 1976, when a vaccination program encountered various public relations problems. Fears of an epidemic proved unfounded.

During the show, our guests share insights about the panic over potential epidemics, including a swine flu scare in 1976, when a vaccination program encountered various public relations problems. Fears of an epidemic proved unfounded.

Time-traveling much farther back, outbreaks of cholera during the 1830s, '40s and subsequent decades caused extreme panic in many Indiana communities.

Take the town of Aurora on the Ohio River, which had a population of 2,000 in 1849. Fourteen deaths from cholera were reported in one day, according to a historical account supplied by Dr. McNiece, an associate professor at the IU School of Medicine. During the next three weeks in 1849, 51 other victims died in Aurora. As a result, 1,600 of the 2,000 residents fled the town.

Take the town of Aurora on the Ohio River, which had a population of 2,000 in 1849. Fourteen deaths from cholera were reported in one day, according to a historical account supplied by Dr. McNiece, an associate professor at the IU School of Medicine. During the next three weeks in 1849, 51 other victims died in Aurora. As a result, 1,600 of the 2,000 residents fled the town.

Also in 1849, the town of Madison reacted to outbreaks of cholera by creating a board of health with the power to quarantine residents and to impose fines on people who brought the disease into the city.

On Hoosier History Live, we have explored some epidemics on previous programs.

In 2009, Bill Beck was a guest for a show about the 1918 influenza epidemic and its Indiana impact. That horrific epidemic, which ravaged North America and Europe, is considered to have been the world's worst flu epidemic; it coincided with - then persisted after - World War I.

In 2012, Hoosier History Live explored various aspects of the polio epidemic, including the involvement of Eli Lilly and Co. in distributing the polio vaccine during the 1950s.

For this show, we broaden the focus and explore those epidemics, as well as several others.

Learn more:

- Black Cholera comes to Central Valley of America in 19th Century - Walter Daly, M.D.

- Flu lessons from history - Indianapolis Star.

- Polio epidemic during the 1940s and '50s - Hoosier History Live show.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- The influenza epidemic of 1918 - National Archives.

- The Great Pandemic.

- 1821 Plague Cemetery, Indianapolis.

- Damien Center.

- Ancestry, Cholera Epidemic in Dearborn County, 1849-1851.

© 2015 Hoosier History Live! All rights reserved.

Hoosier History Live!

P.O. Box 44393

Indianapolis, IN 46244

(317) 927-9101