Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

March 2, 2019

Historic women in science: encore

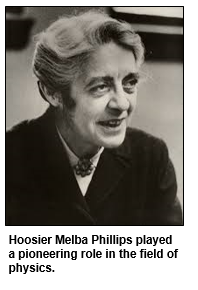

Women from Indiana became pioneers in sciences ranging from physics to home economics during the early and mid-1900s. But they confronted myriad challenges, and their trailblazing efforts often have been ignored.

Hoosier History Live strives to fill in this historical void as we salute Women's History Month with this encore broadcast (original air date: March 11, 2017) of a show that spotlights the innovations of - and obstacles confronted by - a physicist from southern Indiana who pioneered new theories (but whose career was stalled because of McCarthyism during the Cold War) and two women associated with Purdue University who were pioneers in "bringing science into the home." One of them traveled across the Hoosier state during the World War I era to share research with farm women.

Nelson's guests include:

Jill Weiss, digital outreach manager at the Indiana Historical Bureau. She shares insights about Melba Phillips (1907-2004), a native of Hazleton, Ind., who became an internationally acclaimed physicist, worked to improve science education and, according to Jill, "advocated for women's place at the forefront of science research." Following World War II, Phillips and other scientists organized to prevent nuclear war. She was fired from university posts, though, after being accused of advocating subversive positions.

- And Angie Klink, a Lafayette-based author and historian whose eight books include Divided Paths, Common Ground (Purdue University Press, 2011). It is a dual biography of Mary Matthews, who became the first dean of home economics at Purdue University, and Lella Gaddis, the first state leader of home demonstrations in agricultural extension.

When Matthews was initially appointed a department chair of home economics in 1912 prior to becoming Purdue's first dean of the subject, "she had little support from the men in power at Purdue," Angie writes.

Melba Phillips, the physicist, encountered enormous challenges during her long career, but she rebounded and became the first woman president of the American Association of Physics Teachers in 1966.

Phillips, who had studied under Robert Oppenheimer and went on to write two physics textbooks, was living in Petersburg, Ind., when she died at age 97. During the 1950s, she refused to testify before a subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee that was investigating internal security.

Jill's blog about her is titled "Melba Phillips: Leader in Science and Conscience." Phillips also is the subject of an episode of the IHB podcast Talking Hoosier History, which Jill helps produce.

As described in our guest Angie Klink's book Divided Paths, Lella Gaddis "tooled down the country roads past Indiana cornfields" to bring the latest science about vitamins, food preservation, sanitation and other topics to farm wives. On the running board of her Model T, Gaddis propped her demonstration suitcase - and held onto it as she traveled on the rural roads.

Divided Paths also tells the story of an unconventional "lady farmer," as Virginia Claypool Meredith was called during the late 1800s and early 1900s. During our show, we also will explore her pioneering career, which included becoming the first woman on Purdue's board of trustees in 1921.

When Virginia Claypool Meredith was 33 years old in 1882, she had to take over the running of a 115-acre cattle and sheep farm near Cambridge City, Ind, when her husband died unexpectedly, according to Angie's book. "She became a nationally recognized agricultural speaker and writer."

Roadtrip: Adams Mill in Carroll County

Adams Mill is filled with historic treasures on all its floors, including a Conestoga Wagon and a canvas bathtub used by pioneers as they traveled out west. The mill also has the original milling equipment and artifacts from when it housed a post office. And just down a winding country road is the Adams Mill Covered Bridge, built in 1872.

Adams Mill was placed into the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. Open for tours, it is a fascinating look back in time when mills served the towns and outlying regions where they were located. And it's also one of the few survivors in the 21st century. At one time saw mills and grist mills dotted the landscape of Indiana, necessary for both grinding grain and sawing lumber for building. Now just about 13 remain.

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Serita Borgeas

- Margaret Sabens

- Marjorie and James Kienle

- Robin Jarrett

- Susan Orr

- Jennifer Q. Smith

- Wendy Boyle

March 9, 2019 - coming up

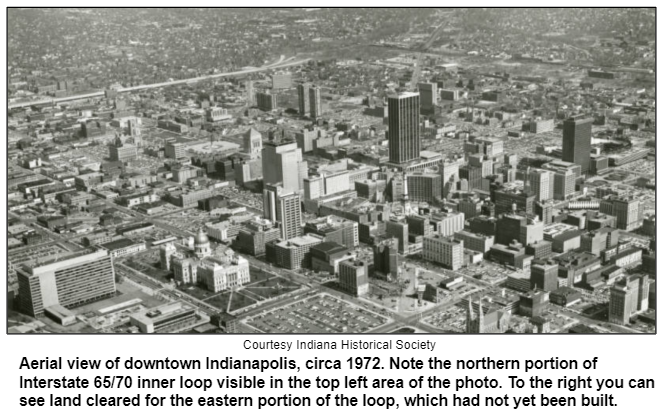

Interstate highway construction and its impact on Indianapolis

It's the largest engineered structure humans have ever built, covering a land mass the size of the state of Delaware. Along with the Great Wall of China, it's one of the few human creations that can be seen from space. In its entire length, it stretches 46,876 miles.

And you probably use it on a regular, if not daily, basis.

And while the nation's extensive network of well-engineered Interstate highways, which took over four decades to build, has brought undeniable benefits in the form of greater road safety and efficiency for personal travel and commerce, there's a darker side to the story.

Often unacknowledged by lovers of the open road are the high costs that Interstate highway construction wrought upon urban centers, where tens of thousands of American citizens lost their property to eminent domain, saw their neighborhood houses, schools and businesses bulldozed, and found themselves living next to an endless stream of noisy traffic.

Hoosier History Live associate producer and guest host Mick Armbruster will delve into the impact of Interstate construction on the city of Indianapolis, looking at how it disrupted the lives of urban residents during the building phase and had long-lasting, far-reaching impacts on the city's development. Joining Mick in studio to discuss Indianapolis highway history will be:

- Jordan Ryan, who coordinates the Indianapolis History Project at the Indiana Historical Society. Jordan has conducted archival research into routing decisions made during the Interstate planning process in the late 1950s that brought the combined 65/70 inner loop to downtown Indianapolis, examining how those choices affected urban neighborhoods.

- Paula Brooks, who as a child experienced firsthand the impact of Interstate construction on her Indianapolis neighborhood, Ransom Place. She is involved in current advocacy efforts regarding environmental justice and also works with Rethink 65/70, which seeks to influence plans by the Indiana Department of Transportation to redesign the Interstate 65/70 inner loop.

- And Garry Chillufo, founding member and current president of Historic Urban Neighborhoods of Indianapolis (HUNI), a coalition that supports older neighborhoods by working with local government and serving as a forum for urban residents. Garry is also involved with the work of Rethink 65/70.

The dream of a national highway system that would unite the sprawling territory of the United States goes back all the way to the founding fathers; it was President Thomas Jefferson who signed the act establishing a National Road in 1806, with the goal of connecting Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River.

But it was the explosion of automobile ownership in the 1920s that spurred the massive growth in paved, graded highways that could accommodate high volumes of traffic traveling at ever increasing speeds. Eventually, the National Road would stretch through Indiana and the city of Terre Haute, where its intersection with Highway 41, a major north-south thoroughfare, would earn the city the nickname "Crossroads of America," which was later was associated with Indianapolis and the state at large.

Road building did not stall out during the Great Depression, thanks to billions provided by New Deal programs that put drought-stricken farmers to work constructing hundreds of miles of new highways. But it was during the era of post-war prosperity in the 1950s, with automobile ownership rising faster than the tail fins on Cadillacs, that highway construction got into high gear.

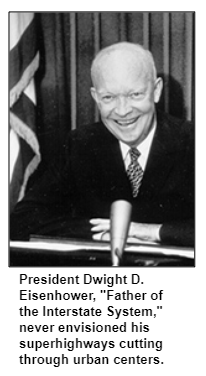

But Eisenhower never envisioned the Interstate highways reaching into the inner urban core. Modeled on the Autobahn, his proposed system would have carried traffic only between and around cities, not through them.

Under pressure from members of Congress, however, who believed that urban freeway segments were essential to the needs of their constituents, Eisenhower relented and went forward with plans that brought major highways through the heart of America's cities - and left destruction and social upheaval in their wake.

Some Interstate history facts:

- The Interstate highway system is the biggest public works project in the history of the United States.

- Missouri was the first state to begin building a segment of Interstate highway, reconfiguring U.S. 40 into what was later designated the I-70 Mark Twain Expressway. The work began on on August 13, 1956.

- In 2002, native Hoosier David Letterman launched a humorous campaign to rename I-465 in his honor. "Honest to God, would it kill ya to do this?" the comedian asked in reference to renaming the roadway the "David Letterman Expressway."

© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|