Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

April 6, 2019

Distinctive historic homes

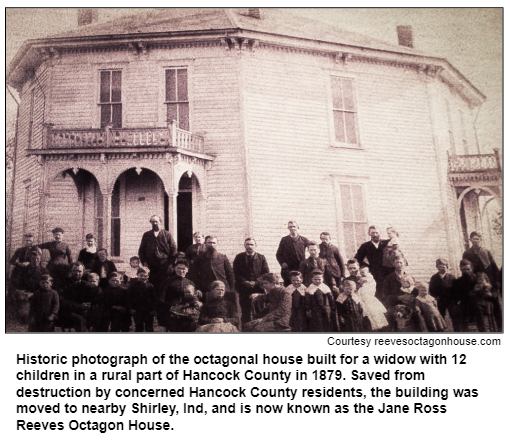

A rare octagon-shaped house was built for a widow with 12 children in a rural part of Hancock County in 1879. She saved silver dollars until she accumulated more than $2,300, enough for construction of the distinctive house for her large brood.

Now known as the Jane Ross Reeves Octagon House, the historic residence had deteriorated alarmingly and almost burned in a firefighter training exercise before several residents of the town of Shirley purchased the farmhouse during the late 1990s. They moved it into Shirley near the railroad depot. A 20-year restoration project has resulted in a house that's now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and can be toured by appointment, beginning every April.

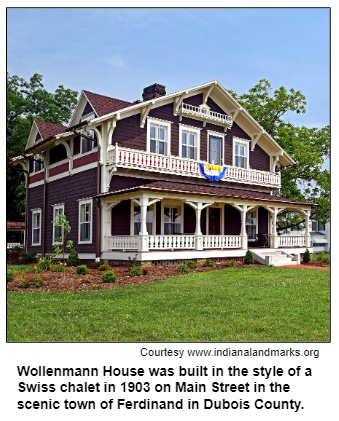

One unusual detail of the house reflected Dr. Wollenmann's medical practice, which he ran out of the home. He had a sliding panel installed in the front door so that he could assess the illness of patients before bringing them into his house. In the early 1900s, his son raised 11 children in the residence.

The Wollenmann House also was imperiled - it was placed on the 10 Most Endangered Sites list of Indiana Landmarks in 2010 - before being rescued. Purchased by a small group of Ferdinand residents, who then donated it to the Ferdinand Historical Society, the Wollenmann House also is listed on the National Register. Today, the distinctive chalet is home to Soup-N-Such, a café whose owners live the upstairs portion, where original features include a claw foot bathtub.

As we explore distinctive historic structures built as homes (or that have become residences), Nelson will be joined by:

Hancock County historian Brigette Cook Jones, who will discuss the Jane Ross Reeves Octagon House, which is celebrating its 140th anniversary this year. With 16 rooms, including several that are pie-shaped, it is believed to be one of just five octagonal homes that survive in Indiana. Like round barns, octagonal houses fell out of style.

- And Diane Hoppenjans, past president of the Ferdinand Historical Society and vice president of Dubois County Tourism. Diane and her husband Alvin were among the residents who purchased the Wollenmann House to save the historic structure before donating it to the local historical society, which continues to own the chalet.

During our show, Diane also will discuss another landmark in Ferdinand, which is in a region of Indiana known for its German heritage. It's a historic structure that's also on the town's Main Street; in the 19th Century, it was the residence and store of a family in the mercantile business.

In addition, Diane will describe a community-wide project in which she's involved: the restoration of the historic Chapel of Our Sorrowful Mother. Built on a hill in the 1870s by German immigrants, the Catholic chapel overlooks St. Ferdinand Parish. As once was the case with the historic houses we will explore on this show, the chapel has deteriorated dramatically.

The Jane Ross Reeves Octagon House had decayed to the point that it essentially functioned as a run-down barn, housing hogs and cattle, before its move to Shirley and the painstaking renovation. Aside from its shape, the house has other distinctive features: it has four chimneys, and all 16 rooms have closets.

In addition to describing the colorful history of the octagonal house, Brigette will share details about a project underway at a site in Hancock County that's well-known to Hoosier history lovers: the James Whitcomb Riley Boyhood Home and Museum in Greenfield. Riley (1849-1916), the Hoosier poet, grew up in the house, which is on the National Register. A new, multi-use building is being constructed on the home museum's grounds.

Roadtrip: Learn about the Amish and Mennonites at Menno-Hof in Shipshewana

Did you ever wonder why the Amish dress as they do and don't drive cars, or what is the difference between the Amish and the Mennonites?

Guest Roadtripper and retired independent bookstore owner Kathleen Angelone invites us on a trip to visit Menno-Hof, a non-profit information center located in Shipshewana, Ind., near the far north-eastern corner of the Hoosier state. The Menno-Hof museum teaches visitors about the faith, life and history of the Amish and Mennonite communities.

Naturally enough, given the importance of agriculture for these two groups, the center is located in a huge red barn, where you can start your visit by watching a movie to see how the local community erected it in a one-day barn raising.

The Menno-Hof center relates the history of the Anabaptist movement, which dates to 16th century Switzerland; the Amish and Mennonites are direct descendants of early Anabaptists. The first several exhibits of the museum recreate important locales in Anabaptist history, including a dungeon where believers were tortured.

The center also covers more recent history, such as the Amish and Mennonites coming to America and early settlements. Kathleen says that there are loads of interactive displays which are "both interesting and informative."

And if shopping is your thing, you'll want to check out the museum's gift shop, which features handcrafted items made by local Amish and Mennonites.

History Mystery

Miniature houses are the focus of a museum in an Indiana city. In addition to tiny homes, artifacts at the museum include historic dollhouses and room boxes, including some created in the 1860s. Other collectibles also are exhibited.

The museum, which opened in the early 1990s, is located on Main Street in the Indiana city.

Question: What Indiana city is home to a museum focusing on miniature houses?

Please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air, and please do not try to win if you have won any other prize on WICR during the last two months. You must be willing to give your first name to our engineer, you must answer the question correctly on the air and you must be willing to give your mailing address to our engineer so we can mail the prize pack to you. Prizes: four passes to the Indiana History Center, courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, and a gift certificate to Story Inn, courtesy of Story Inn.

Please email molly@hoosierhistorylive.org if your business or organization would like to offer History Mystery prizes.

That "Sinky" feeling: talking about a Hoosier musical great

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Perry and Melanie Hammock

- Jim and Bonnie Carter

- Barbara and Michael Homoya

- Noraleen Young

- Barbara Wellnitz

- Phil and Pam Brooks

- Russ Pulliam

- Roz Wolen

April 13, 2019 - coming up

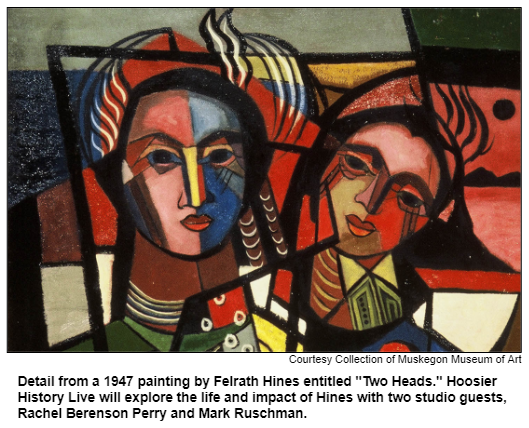

An artist who confronted segregation, and other painters

It may seem remarkable that his abstract artwork often reflected harmony and balance, given the struggles he faced in establishing himself as a prominent artist.

Today, paintings by Hines (1913-1993) are exhibited at museums across the country, including the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. and the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. For several years, Hines worked with Georgia O'Keeffe as her private paintings restorer.

We will explore the life and impact of Hines - as well as other artists - with two studio guests:

- Rachel Berenson Perry, author a new book, The Life and Art of Felrath Hines: From Dark to Light (IU Press and Indiana Historical Society Press). Rachel, who lives in Brown County, is the former fine arts curator for the Indiana State Museum. She has been a frequent guest on Hoosier History Live shows about other Indiana artists, including T.C. Steele and William Forsyth, the subjects of some of Rachel's other books.

- And Mark Ruschman, senior curator of art and culture at the Indiana State Museum, who put Rachel in touch with Hines' widow several years ago. In June, the State Museum will open an exhibit titled It's About Time: The Artwork of Felrath Hines.

As a 13-year-old boy, Hines received scholarships to attend special Saturday classes at what was then called the Herron Art Institute. Despite segregation in Indianapolis schools and public places, Herron had established an open door policy at its inception in 1903 and did not discriminate on the basis of race, according to Rachel's book. At Herron, young Hines studied painting and drawing.

During his career, Hines fought against, as Rachel puts it, "being pigeonholed as a black artist" - even when turning down opportunities for his paintings to be included in exhibits of African American artwork hurt his career.

© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|