Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

May 11, 2019

Willy T. Ribbs on making Indy 500 history

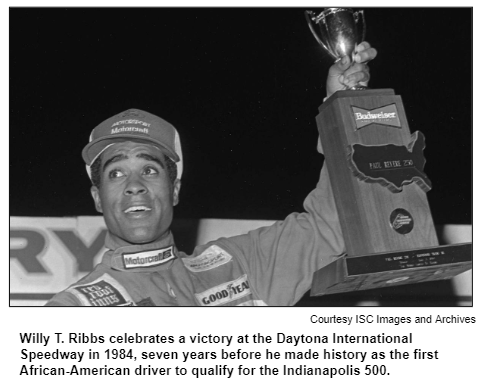

He's referring to the electrifying moment on May 19, 1991 when, at the last possible opportunity, Willy T. Ribbs became the first African-American driver to qualify for the Indianapolis 500. An earlier qualification attempt by Willy, who was driving for Derrick Walker Racing, had failed because of engine troubles.

His trailblazing achievement at the Speedway - he eventually finished 32nd in the Indy 500 in 1991 - followed years of struggles, including harassment and even death threats when he competed in NASCAR races beginning in the late 1970s. His challenges are recounted in Uppity, a documentary film that had its world premiere in Indianapolis last year.

Willy, 64, will discuss his life and racing career as Nelson's guest by phone from Texas, where he lives today. The son of an amateur race driver and plumbing contractor, Willy grew up in San Jose, Calif. In Uppity, Willy recalls how he announced as a 9-year-old that he wanted to be an Indy 500 or Formula One driver - even though he had no African-American role models.

Like Willy, several other former Indy 500 drivers have been Hoosier History Live guests. They include Willy's friends Lyn St. James, who in 1992 became the second woman driver in the Indy 500 (Janet Guthrie was the first, in 1977) and Derek Daly, the Irish racer who settled in central Indiana and became a broadcast analyst. In 2016, Merle Bettenhausen was our studio guest to discuss his racing career and the tragedies that befell his family.

As a boy in California, Willy T. Ribbs was intrigued by motorcycle and auto race drivers who were his father's friends. To launch his career, he moved to England during the mid-1970s and competed in various racing circuits.

Uppity takes its title from one of the derogatory words that detractors used to describe Willy after he returned to the United States and sought to advance in auto racing.

"It wasn't a red-carpet ride," he has said of the challenges involved with his racing career. "But it's one that I'd do over again."

In addition to his history-making achievement in 1991 - which was the 75th running of the Indy 500 - he competed at the Speedway two years later. In 1993, Willy finished 21st in the Indy 500.

Roadtrip: Community mausoleums

Guest Roadtripper Jeannie Regan-Dinius invites us on a journey to the "mansions of the dead," the stately community mausoleums that were built early in the last century and grace the finer cemeteries of Indiana.

As Jeannie explains, the U.S. community mausoleum movement started in Ganges, Ohio in 1907. The buildings were celebrated for their beauty and engineering and hailed as a modern, sanitary means of disposing of a loved one's remains. Unlike private family mausoleums, community mausoleums sold individual niches to members of the public, with no requirement to belong to a particular family or social class.

About 40 community mausoleums were constructed in Indiana between 1907 and 1937, and about 35 remain today. These architectural gems illustrate innovative early-20th-century use of materials such as concrete combined with traditional finishes such as as marble, limestone and granite.

Jeannie's Roadtrip will take us to some of the most architecturally opulent community mausoleums around the Hoosier state. Don't be caught dead missing this fascinating journey to Necropolis!

History Mystery

For many years, women were considered bad luck at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and were prohibited from the pit area and Gasoline Alley. A certain color also was considered bad luck at the race track.

So in 1977, when Janet Guthrie made international headlines by becoming the first woman to qualify for the Indianapolis 500, she deliberately competed in a race car of the "forbidden" color as a gesture of defiance against antiquated traditions.

Question: What was the color?

Please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air, and please do not try to win if you have won any other prize on WICR during the last two months. You must be willing to give your first name to our engineer, you must answer the question correctly on the air and you must be willing to give your mailing address to our engineer so we can mail the prize pack to you. This week's prizes: a Family 4-Pack to the Indiana State Museum, courtesy of the Indiana State Museum, and a pair of tickets to the James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home in Indianapolis, courtesy of the Riley Museum Home.

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Perry and Melanie Hammock

- Jim and Bonnie Carter

- Barbara and Michael Homoya

- Noraleen Young

- Barbara Wellnitz

- Phil and Pam Brooks

- Russ Pulliam

- Roz Wolen

- Marion Wolen

May 18, 2019 - coming up

Brothels and streetwalkers in pre-1920 Indy: encore

To examine these aspects of the Hoosier state capital's social history, Nelson's studio guest on this encore show (originally broadcast July 8, 2017) is Paul Mullins, a popular professor in IUPUI's Department of Anthropology.

A historical archaeologist, Paul has researched and written about pre-1920 prostitution as part of a larger project titled "Invisible Indianapolis: Race, Memory, and Community Memory in the Circle City."

Along with co-director Susan Hyatt and a team that includes both undergraduate and graduate students, Paul has published the project's findings in a blog called Invisible Indianapolis.

The project's overarching goal: to show the historical impact of seemingly invisible urban social factors such as racial redlining, highway construction and gentrification.

- An area bounded by what is today Park Avenue (then called Liberty Street) and Market, East and Washington Streets.

- A district at the site of what is now another hospitality building, the Indiana Convention Center. The district ran along Senate Avenue near Georgia Street.

"Prostitution probably always was an element of the early cityscape, but some of the earliest evidence for houses of prostitution comes in the 1850s," Paul writes in the blog.

He quotes an 1857 newspaper account of a shooting at a brothel managed by a "mysterious woman." After the shooting, he adds, the illicit business "became the target of mob justice when [the woman's] brothel was set afire by a mob of more than 200 people."

"The desperation of some women working as prostitutes was documented in a string of suicides and suicide attempts," Paul reports.

Paul Mullins is a past president of the Society for Historical Archaeology. For several years, Paul and his students could be seen during the summer months excavating sites near the IUPUI campus. Paul was a Hoosier History Live guest in 2009 when he was leading an excavation on the site of the long-demolished home of Madam Walker, the wealthy African-American entrepreneur and philanthropist.

According to Paul's research for Invisible Indianapolis, prostitutes often worked "in and around" Union Station during the late 1800s and early 1900s. (Before majestic Union Station opened during the 1880s, its predecessor, Union Depot, was the first train station in the country where competing railroad lines came together.)

Near the bustling train station, brothels were located among saloons and stores on South Street.

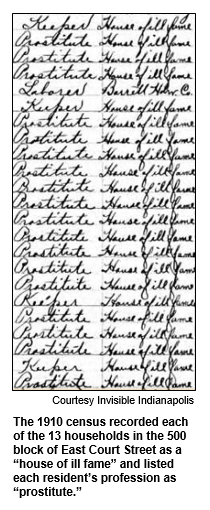

Farther east, a bygone street named East Court Street (now a parking lot between East and Park) had a cluster of brothels that Paul describes as "the city's most prominent concentration" of such businesses. In 1898, a Sanborn map "identified nearly every structure on East Court as a 'female boarding house,'" Paul writes, noting that at least 10 of these 16 homes listed in the 1899 city directory were brothels.

His blog describes attempts by local churches to encourage police raids of the brothels. Some of the churches also were active in the temperance movement.© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|