Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

July 6, 2019

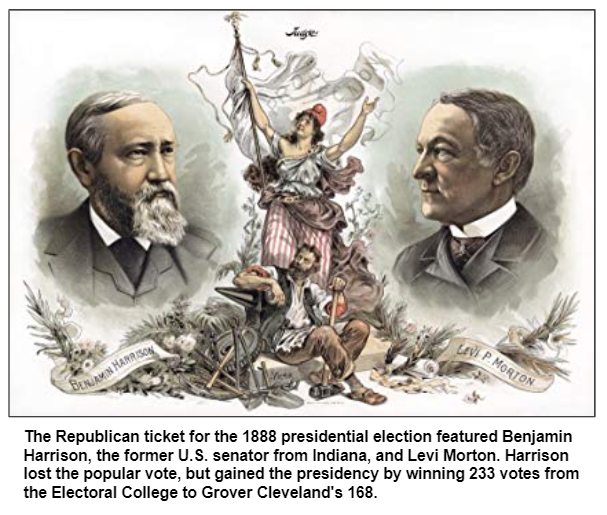

Electoral College upset, souvenir hunters and no campaigning: 1888 and 1892 presidential races

Because of the attention focused on the Electoral College in the 2016 presidential race - in which the winner did not gain the most popular votes - it may not be surprising that a similar situation unfolded in 1888.

That's what happened in 1892 - in sharp distinction to the current situation in which intense campaigning is in full swing more than 18 months before voters go to the polls.

Both the 1888 and 1892 campaigns featured Benjamin Harrison of Indianapolis as the Republican candidate for the White House. And both unfolded during an era - stretching from the 1870s through the 1920s - in which Indiana was regarded nationally as a "swing state" in presidential elections.

As evidence: Harrison did not carry his home state in 1892 (a majority of Indiana voters preferred his Democratic opponent, Grover Cleveland), although Harrison, a former U.S. senator from Indiana, won the Hoosier State in 1888. His "front porch campaign" that year - based out of his Italianate home that is now part of the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site at 1200 N. Delaware St. - resulted in scores of souvenir hunters who tore off pieces of the property's wooden fence. Caroline Scott Harrison, who would become the nation's first lady, is said to have remarked: "If we don't go to the White House, we'll go to the poor house, with all of the repairs we'll have to make."

To share insights about colorful and intriguing aspects of Harrison's presidential campaigns, Nelson will be joined by Ray Boomhower of the Indiana Historical Society, the author of the new biography Mr. President: A Life of Benjamin Harrison (IHS Press).

In contrast, the 1888 campaign - which also featured Harrison against Cleveland - was a lively affair. One of the more memorable publicity ploys: Harrison's supporters built a massive, steel-rigged, canvas ball, covered it with campaign slogans and travelled over 5,000 miles with it to the candidate's Indianapolis home.

Harrison achieved the presidency that year by winning the Electoral College (with 233 votes to 168 for Cleveland), although he lost the popular vote. That was the third of five times in American history in which the loser of the popular vote won the Electoral College - and, as a result, the White House.

Of the six vice presidents who have been elected from Indiana, four of them achieved office during the era when Indiana was considered a swing state in national elections and was therefore courted by both parties. The Hoosier vice presidents during that era include two Democrats - Thomas Hendricks (who was in office for one year only, 1885) and Thomas R. Marshall (who served from 1913-1921) - and two Republicans, Schulyer Colfax (veep from 1869-1873) and Charles Fairbanks (1905-1909).

In the 1888 presidential campaign, Benjamin Harrison gave "more than 80 extemporaneous talks to more than 300,000 visitors to Indianapolis" between early July and late October, according to Ray's biography. Marching bands often escorted the delegations of visitors from a city park to the Harrison home on North Delaware Street. Delegations included Union veterans of the Civil War, African-American supporters and railroad workers.

Four years later, some key Republican Party leaders declined to help Harrison. From the start of his presidency, Ray writes, Harrison "stood steadfast … in making sure that qualified individuals - not party stooges - received appointments to key government positions."

Because of Caroline Scott Harrison's illness, the 1892 presidential contest "paled in comparison in every way with the one four years before," according to Mr. President. After she died on Oct. 25, grief-stricken President Harrison accompanied his wife to Indianapolis for her burial at Crown Hill Cemetery. Two weeks later, he lost his bid for re-election, with Cleveland defeating him both in the popular vote and in the Electoral College.

Roadtrip: Jackson County History Center in Brownstown

Guest Roadtripper Mary Beth Glick, Bartholomew County resident and Cummins retiree, tells us that her interest in learning about her German farming and merchant ancestors in Bartholomew and Jackson Counties led her to discover the Jackson County History Center in downtown Brownstown in southern Indiana.

Mary Beth begins our trip to the History Center with a visit to the Nentrup Trading Post, which was erected about 1840 by Mary Beth's ancestors. Other points of interest in the History Center's compound include an old bridge constructed of trusses from the Vallonia Canning Factory, a schoolhouse and a pioneer cabin.

For those who trace their ancestry to the region, the Jackson County Genealogy Library is adjacent and available to explore. The library offers classes in genealogical research as well as special-interest group meeting for those with German and Irish heritage. Check out their website for the current meeting schedule!

To hear more about Mary Beth's own research into her German ancestors and why they settled in Jackson and Bartholomew counties, be sure to join her on this fascinating Roadtrip!

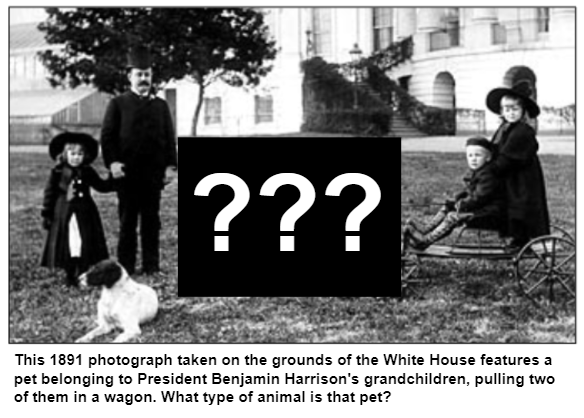

History Mystery

Benjamin and Caroline Scott Harrison's young grandchildren, who lived with them in the White House during the late 1880s and early 1890s, had an unconventional pet. Their pet was an animal typically seen on farms. Although the pet was not a horse or pony, it often was seen on the White House lawn pulling the president's grandchildren in a wagon or cart for playful rides.

In a rollicking episode described by the national press, the pet once broke loose and ran through the White House gates. President Harrison chased the pet down Pennsylvania Avenue, much to the astonishment of onlookers.

Question: What animal was the unconventional pet of Benjamin Harrison's grandchildren?

Hint: The presidential chase - with Harrison holding his tophat as he ran - inspired a children's book published in 2018.

Please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air, and please do not try to win if you have won any other prize on WICR during the last two months. You must be willing to give your first name to our engineer, you must answer the question correctly on the air and you must be willing to give your mailing address to our engineer so we can mail the prize pack to you. The prizes this week are a Family 4-Pack to the Indiana State Museum, courtesy of the Indiana State Museum, and a gift certificate to Story Inn in Brown County, courtesy of Story Inn.

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Perry and Melanie Hammock

- Jim and Bonnie Carter

- Barbara and Michael Homoya

- Noraleen Young

- Barbara Wellnitz

- Phil and Pam Brooks

- Russ Pulliam

- Roz Wolen

- Marion Wolen

- Richard Vonnegut

- Robin Jarrett

July 13, 2019- coming up

White River history

During the 1820s, it was a key factor in determining the site of the new city of Indianapolis. But there was a major misconception that became obvious when a steamboat got stuck and became the object of ridicule.

Soon it became an aquatic dumping ground, with complaints about pollution surfacing by the 1880s in both Marion and Hamilton Counties. During the early 1900s, it was the setting for baptism events that involved hundreds of people on Sundays; the practice ended because of typhoid outbreaks.

In the mid-1970s, an Indianapolis-based rock music radio station sponsored hippie-oriented raft races in which competitors paddled aboard discarded sofas, debris and other makeshift watercraft.

In recent decades, however, significant efforts have been undertaken to clean up the White River.

- Kevin Hardie, executive director of the Friends of the White River, who has been involved with the nonprofit since its inception in 1985. His staff role was created in 1999 after a controversial fish kill episode made national news; a chemical discharge from a manufacturing plant in Anderson was blamed for killing as many as 5 million fish.

- Hamilton County historian David Heighway, who has written blog posts about a wide range of aspects of White River history that have had an impact on residents of Noblesville and other nearby towns. The White River was used as a power source by grist mills and other businesses from the earliest eras of the communities, according to David. His research even has uncovered newspaper accounts in 1892 that describe sightings of a Loch Ness-style monster in the river.

- And Alex Umlouf, co-chair of the White River committee of Reconnecting to Our Waterways (ROW) and a former staff member of White River State Park. Both Kevin and Alex conduct on-water tours of the White River.

Assumptions that the White River would be navigable as a major trade route were a significant factor when state leaders in the 1820s selected the site of the Indiana's new capital city.

The humiliating episode, known as Hanna's Folly, convinced Hoosiers that the river could not handle large ships of any kind.

Near the river's edge just west of downtown Indianapolis, Kingan & Co. opened a huge meat-packing operation in the late 19th century; environmentalists eventually criticized the operation and other industries for using the river as a way to dispose of waste.

"As late as the 1950s, state environmental employees sampling the river using a rowboat would have animal entrails hanging from the oars while there were on the river downtown," according to our guest Kevin Hardie.

Colorful watercraft were seen on the White River during the WNAP Raft Races that began in July 1974 and drew thousands of spectators to Broad Ripple Park. Organized by the former WNAP-FM, a radio station popular with young listeners, the raft races were described as "Central Indiana's version of Woodstock."

The White River Vision Plan has been put together to guide decision-making for the next 30 years. According to a recent story published in the Indianapolis Business Journal, the plan encourages the creation of seven recreational "anchor areas" on 58 miles of the White River through Marion and Hamilton counties.© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|