Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or stream audio live from anywhere on WICR Online!

You can listen to recent shows by clicking the podcast links below, or check out our extensive archive of past shows available as podcasts

November 2, 2019

Racial justice in 1820s Indiana: Slave trial and Fall Creek Massacre - encore

Indiana judicial history is not generally known for legal precedents that promote the cause of racial justice.

But with host Nelson Price away, we're drawing upon our rich archive of previously aired episodes to bring you a special encore show focusing on two landmark legal cases of racial justice in early 19th century Indiana.

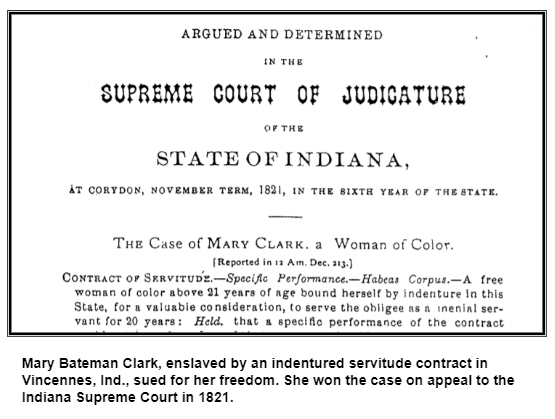

In 1821, Mary Bateman Clark, a young African-American woman living in Vincennes, made history when her lawyer filed a lawsuit seeking her release from an "indentured servitude" contract with one of the most prominent men in the new state of Indiana. The contract required Clark to cook, clean and sew for Gen. Washington Johnston and his family for 20 years. Her only pay was housing, food and clothing.

The case, which made its way to the Indiana Supreme Court, involved determining whether such "indentured servitude" contracts violated the state's Constitution as a form of slavery. Nearly 200 years ago this month - on Nov. 16, 1821 - the state Supreme Court ruled in Clark's favor and ordered her employer to release her.

Sharing insights about the social history of the era and the landmark case, Nelson is joined in studio by one of Clark's descendants, Indianapolis resident Eunice Trotter. Eunice, a veteran journalist, and her sister Ethel McCane have used their research about their ancestor to do "living history performances" for schools and civic groups across the state.

Sharing insights about the social history of the era and the landmark case, Nelson is joined in studio by one of Clark's descendants, Indianapolis resident Eunice Trotter. Eunice, a veteran journalist, and her sister Ethel McCane have used their research about their ancestor to do "living history performances" for schools and civic groups across the state.

Eunice and Ethel also crusaded for a historic marker in honor of Mary Bateman Clark, which was dedicated at the Knox County Courthouse in 2009. The sisters are Mary Bateman Clark's great-great-great granddaughters.

Nelson and his guest also discuss a similar case involving another young woman, Polly Strong, who also lived in Vincennes in the 1820s and sued to obtain her freedom. She had been enslaved by Col. Hyacinth LaSalle, a prominent Vincennes resident, before Indiana became a state in 1816. LaSalle challenged the new state Constitution, unsuccessfully arguing that it could not be applied retroactively.

Re-enactments of the Polly Strong case have been performed across Indiana under the direction of Corydon historic preservationist Maxine Brown, who has been a guest on Hoosier History Live for a show about her historic restoration of a segregated school in Corydon, as well as a show discussing DNA testing and family ancestry. The restored school, now known as the Leora Brown School, has been the setting for re-enactments of the court cases of Mary Bateman Clark and Polly Strong.

Just three years after the Mary Bateman Clark trial, another milestone Indiana legal case set a precedent for racial justice in the United States.

When a group of white men were found guilty by a jury and executed for the slaughter of nine Native Americans in March 1824, it was the first time that the murders of Indians by whites had been subject to capital punishment under American law.

To explore all aspects of the brutal crimes in the swampy woods of Madison County - where the Native Americans (including three women and four children) were gruesomely murdered - Nelson is joined in studio by David Thomas Murphy, author of the book, Murder in Their Hearts: The Fall Creek Massacre (Indiana Historical Society Press).

To explore all aspects of the brutal crimes in the swampy woods of Madison County - where the Native Americans (including three women and four children) were gruesomely murdered - Nelson is joined in studio by David Thomas Murphy, author of the book, Murder in Their Hearts: The Fall Creek Massacre (Indiana Historical Society Press).

A professor of history at Anderson University, David spent four years researching the massacre, trial and subsequent developments, including the social history of pioneer Hoosiers (Indiana only had been a state for about seven years at the time of the massacre) and of the Native Americans in the region.

"The slaughter in the soggy Indiana creek bottoms created a short-lived but serious national security crisis," David has written, referring to concerns across the country that warfare would erupt across newly developing states.

In researching the tragedy, David explored why the federal government devoted great efforts and resources to prosecuting the perpetrators. David's research required that he reconcile conflicting accounts of the events (the tribal origins of some of the victims remain unclear) as well as the motivations involved in the cold-blooded crimes, which involved shooting some of the Native Americans in their backs and mutilating several of the corpses.

Breaking news: Creepy-crawlies invade WICR studios!

Please share our podcasts!

The world of podcasting is a bit like the Wild, Wild West, and Hoosier History Live is trying to stake its claim on the frontier by spreading our show in the Territories of Apple Podcasts, Google Play, and the like.

No, we're not going to shoot it out at the OK Corral with This American Life, but we need your help if we are going to prosper in this new, somewhat-still-uncharted land.

If you love Hoosier History Live, please help us out by posting our podcasts to your social media accounts and sharing your enthusiasm for particular shows with your friends.

Do you have questions about how to listen by streaming or download our podcasts? Unsure about how to repost? Contact producer molly@hoosierhistorylive.org or webmaster mick@hoosierhistorylive.org.

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/general manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show and in podcasts, contact producer Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our podcast listens are increasing at a rate of 17% a month!

For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show and in podcasts, contact producer Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our podcast listens are increasing at a rate of 17% a month!

Acknowledgments to Visit Indy, Fraizer Designs,WICR-FM, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Bruce and Julie Buchanan

- David Willkie

- Coby Palmer in memory of Gary BraVard

- Tim Harmon

November 9, 2019 - coming up

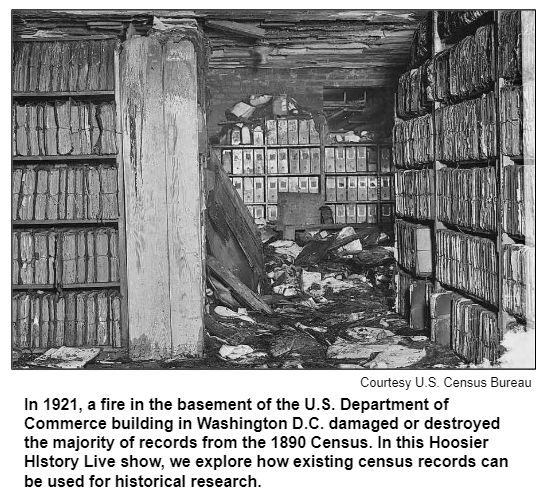

The Census: Tips for using in historic research

As the nation readies itself for the 2020 U.S. Census, Hoosier History Live will take a close look at how records of the previous national headcounts - there have been 23 of them in all, beginning with the first in 1790 - can be used to unearth factual information and illuminate social history, as well as inform us about other aspects of our heritage.

"The first five enumerations listed the number of slaves in each household, and the 1930 enumeration listed whether or not there was a radio in the household," says our guest, Indianapolis-based history researcher Sharon Butsch Freeland.

Sharon regularly uses census information to delve into the history of families and old houses, as well as to investigate historical figures such as the Indianapolis-born wife of Treasure Island author Robert Louis Stevenson. In 2018, Sharon was a guest on our show about the colorful life of Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson. (Sharon's other guest gigs have included our 2017 show about her alma mater, Shortridge High School).

Noting that the census was established by the U.S. Constitution with the purpose of calculating fair representation in the House of Representatives, Sharon adds:

To protect the privacy of living people, census records can't be viewed by the public until 72 years after the census date. Currently, the most recent available for viewing is the 1940 U.S. Census. In 2022, the 1950 U.S. Census will become available.

Some U.S. Census insights, courtesy of Sharon:

- "Digitized census records from 1790 to 1940 can be viewed online at ancestry.com (by subscription) or at familysearch.org for free," she reports. "Ancestry.com is available free of charge at National Archives facilities nationwide and at many public libraries."

- In Indianapolis, the 1870 U.S. Census was collected a second time, during the subsequent year. That's because city leaders had estimated the population to be more than 50,000. When the 1870 Census reported fewer than 41,000, power-brokers in Indianapolis demanded a recount. The 1871 recount was about 19 percent higher.

- In the 1960 U.S. Census, women were asked how many babies they had ever had. Employed people were asked how they got to work: railroad, subway, bus, streetcar, taxi, private auto, car pool, walking, or whether they worked from home. (In 1980, bicycle was added to the list.)

A note about the fire that destroyed most of the 1890 U.S. Census records: The inferno occurred at the U.S. Commerce Building in Washington D.C. Although fragments of information from a few states survived, all of the 1890 records from Indiana were lost in the blaze.

© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|