Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or stream audio live from anywhere on WICR Online!

February 6, 2021

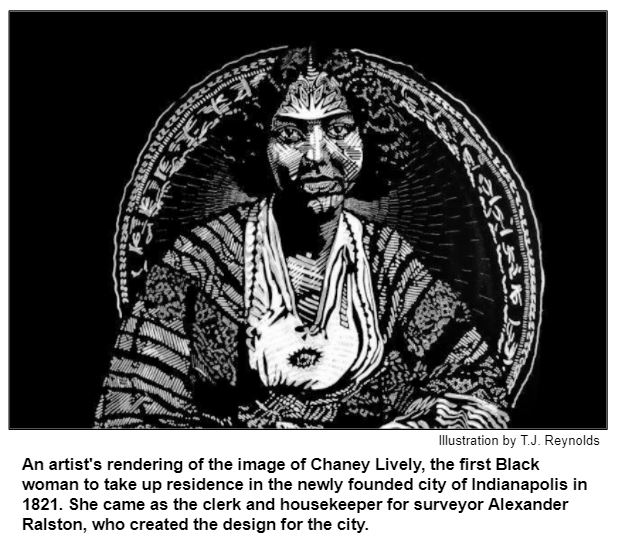

The first woman of color to live in frontier Indianapolis

As Hoosier History Live salutes Black History Month - as well as the Bicentennial era of Indianapolis - we will explore the life of the first woman of color to move to the new Hoosier capital in 1821.

Little had been known about Chaney Lively (1800-1858?), who came to the Indiana wilderness from Kentucky, until our guest researched her life for a cover story in 2019 for Nuvo, the alternative newsweekly. Laura McPhee, the former editor of Nuvo, will join Nelson to share details of her research about Chaney Lively, who arrived as the clerk and housekeeper for surveyor Alexander Ralston, who created the design for Indianapolis.

After Ralston died in 1827, Chaney Lively became the first African-American woman to own a house in the Hoosier capital. At that point the city consisted only of the downtown area known today as the Mile Square, which Ralston designed after coming to Indianapolis in the early summer of 1821.

Laura notes that although Chaney Lively arrived as a free woman of color, she had been enslaved in Kentucky. "It's not clear where or when, but...Ralston purchased Chaney as a slave," Laura wrote. "Most likely, he bought her in Louisville, a major slave trading hub at the time he lived there in the early 1800s."

By researching accounts of Hoosier pioneers, including the multi-volume diary of civic leader Calvin Fletcher, who became the first practicing attorney in Indianapolis, Laura has determined that Chaney Lively was a highly regarded, well-liked resident of the city.

Hoosier History Live explored the life of Ralston, who had been born in Scotland, for a show in 2013; during a show in 2016, we delved into the life of Fletcher, a New England native who, in addition to becoming an attorney, was a banker, state legislator and the owner of vast tracts of property in central Indiana.

By the time Ralston died and Chaney, who lived with him, "moved into her own home in 1827," Laura wrote, "there were less than 60 people of color - men, women and children - living in Indianapolis out of a population of a little more than 1,000."

In 1836, Chaney married John Britton, a former slave who became a barber in Indianapolis. They were among the founding members of Bethel AME Church, which opened in 1841. In Laura's article for Nuvo, she concludes Chaney died in 1857 or 1858 based on a reference by Fletcher to her passing.

Since her departure from Nuvo in 2019, Laura has owned Pen and Pink Vintage, a book shop in the Garfield Park neighborhood specializing in books by women, Indiana authors and Indiana history. At Nuvo, where she was an editor and award-winning writer for nearly 15 years, Laura was known for her coverage of local news and social justice issues.

Laura says she decided to research Chaney Lively's life out of frustration at the scarcity of research undertaken by others.

She determined that when Ralston, who had no known family members in America, arrived in Indianapolis with 21-year-old Chaney Lively, she was described as "a mulatto woman." After Chaney's marriage to John Britton, she is rarely mentioned in diaries and memoirs of early settlers or in Indianapolis newspapers, Laura discovered.

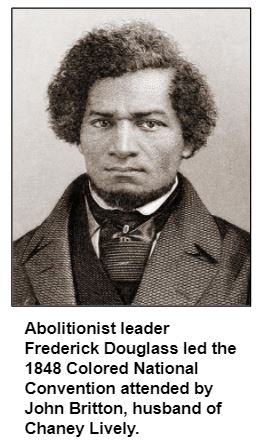

But Britton, a civic leader in the Black community, was mentioned frequently. In 1845, he was a vocal supporter for justice in the death of their neighbor, a Black man who was attacked by a white mob. Britton also was an Indiana delegate to the 1848 Colored National Convention initiated by Frederick Douglass, according to Laura's research.

Chaney and John Britton had a daughter, Eliza. Since her Nuvo article was published, Laura McPhee has been searching for their descendants.

Roadtrip: Waveland - the boyhood home of T.C. Steele

Guest Roadtripper Tim Shelly, an attorney at Warrick & Boyn law firm in Elkhart and former board chairman of Indiana Landmarks, suggests a trip to the small historic town of Waveland in the southwest corner of Montgomery County, about an hour west of Indianapolis.

Waveland began as an overnight stopping point along the early pioneer route that connected Crawfordsville and Terre Haute. The area's rich history includes military excursions led by General William Henry Harrison culminating in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811.

Waveland eventually became home to the Waveland Academy, where T.C. Steele enrolled at the age of 12, and where he began teaching drawing a year later. The house where the boy lived who would grow up to become one of the great Hoosier painters was recently restored as a retreat for artists, art educators, historians and preservationists.

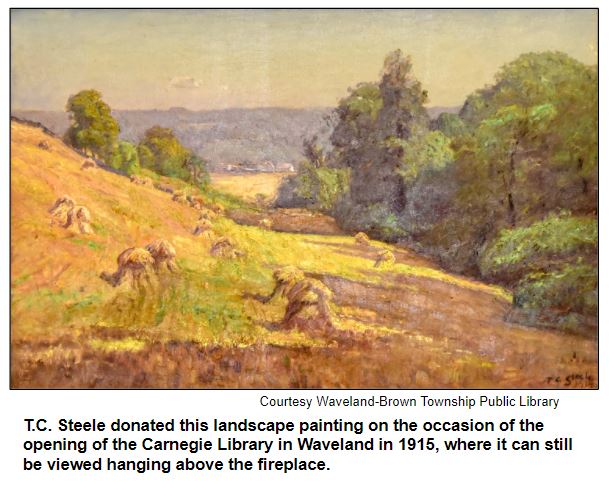

Tim tells us that another must-see stop on any tour of T.C.Steele-related sites in Waveland is the town's public library, constructed in 1916, which is a prime example of Carnegie Library architecture. Notably, Steele donated a large landscape painting on the occasion of the library's dedication, and this outstanding painting still hangs in the library and is alone worth a trip to Waveland.

And for those who enjoy spending time in nature, Tim tells us that Waveland serves as a central starting point for visiting Turkey Run and Shades State Parks, along with Indiana's most popular canoeing, kayaking, and tubing waterway, Sugar Creek, all just a few miles away.

Be sure to join Tim on this exciting roadtrip into Hoosier history, art and nature!

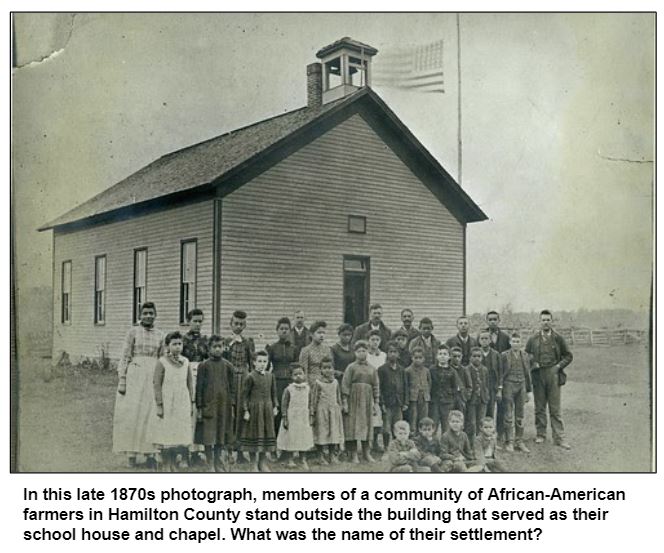

History Mystery

During the 1830s, a group of free African-American pioneers came from the South - primarily North Carolina and Virginia - to Indiana's Hamilton County and founded a settlement of farm families.

Other families of Black and mixed racial heritage gradually joined them at the community in the northern part of Hamilton County. The settlement reached its peak population during the late 1800s, when it included more than 250 residents.

The historic settlement, one of the early Black communities in rural Indiana, no longer exists. But there are some tangible reminders in northern Hamilton County, including a cemetery and a 19th century chapel. Descendants of the Black pioneers return from across the country for annual reunions, usually during Fourth of July weekend.

Question: What is the name of the African-American pioneer settlement in northern Hamilton County?

The call-in number is (317) 788-3314. Please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air, and please do not try to win if you have won any other prize on WICR during the last two months. You must be willing to give your first name to our engineer, you must answer the question correctly on the air and you must be willing to give your mailing address to our engineer so we can mail the prize pack to you.

The prizes this week are Two tickets to the Indiana State Museum, courtesy of the Indiana State Museum, and two tickets to the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site, courtesy of the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site.

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/general manager, (317) 927-9101

Mick Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show and in podcasts, email molly@hoosierhistorylive.org, or call (317) 927-9101 for information. Our podcast listens are increasing and we are being distributed on Indiana Memory and the National Digital Public Library. Grow with us as our podcast and internet presence expands! Thanks also to Visit Indy, Fraizer Designs, WICR-FM, Henri Pensis, Genesis Brown, Kielynn Tally, Heather McIntyre, Justin Clark, and many other individuals and organizations.

For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show and in podcasts, email molly@hoosierhistorylive.org, or call (317) 927-9101 for information. Our podcast listens are increasing and we are being distributed on Indiana Memory and the National Digital Public Library. Grow with us as our podcast and internet presence expands! Thanks also to Visit Indy, Fraizer Designs, WICR-FM, Henri Pensis, Genesis Brown, Kielynn Tally, Heather McIntyre, Justin Clark, and many other individuals and organizations.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Georgia Cravey and Jim Lingenfelter

- Ann Frick

- Yetta Wolen

- In memory of William G. "Bill" Mihay

- Dr. William McNiece

- Michael Freeland and Sharon Butsch Freeland

- David E. and Lynne J. Steele

- Stacia Gorge

- Ann Frick

- Margaret Smith

- Rachel Perry

- Tom and Linda Castaldi

- Serita Borgeas

- Tom Swenson

- Doug Winings

- Theresa and Dave Berghoff

- Dr. Geoffrey Golembiewski

- Jeanne Blake in memory of Lenny Rubenstein

- Chuck and Karen Bragg

February 13, 2021 - coming up

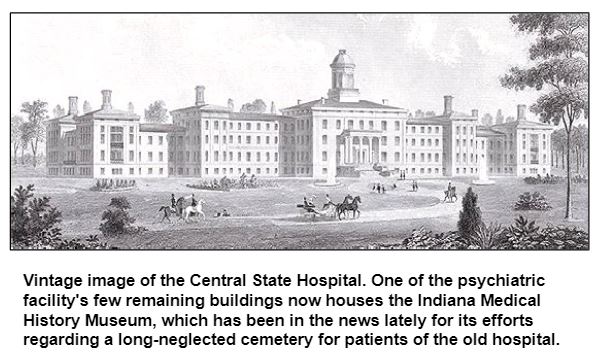

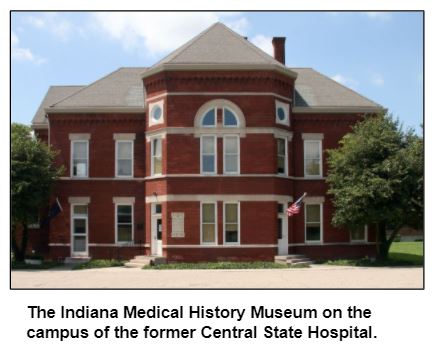

A distinctive cemetery and efforts to humanize former Central State patients

Since our show in 2019 about the Indiana Medical History Museum, news has unfolded related to the museum, which is housed in a building that was part of the historic campus of the former Central State Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Indianapolis that closed in 1994.

When Sarah Halter, executive director of the museum, is Nelson's guest, she will provide updates about the cemetery project. Some aspects have been resolved, according to Sarah.

The remains of the patients affected by the utility work have been carefully exhumed by archaeologists and will be reinterred elsewhere. But other aspects of the museum's cemetery initiatives have yet to reach a resolution. The cemetery is on land owned by the city and used by the police department for its horse patrol.

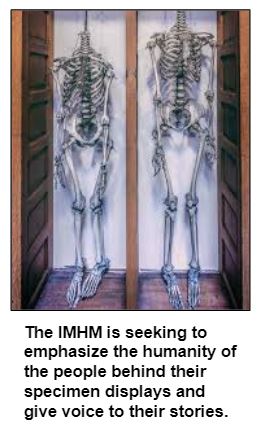

They include, she says, "a new, permanent re-interpretation of our specimen collection that emphasizes the humanity of these specimens and tells the stories of the people from whom they came."

In addition to the museum's exhibits conveying the stories of patients at Central State, many of the personal stories now can be viewed online, with new accounts added periodically.

"We hope that these projects will not only re-humanize the patients, who were too often left out of the story, but also combat stigma and foster compassion and respect for all people, past and present, who experience mental health issues," Sarah says.

The museum is housed in a brick structure once known as the Old Pathology Building. During the 1890s, brain research considered groundbreaking for its era was conducted in clinical labs in the building, which also had an autopsy room and an amphitheater for lectures to medical students.

During our show, Sarah will describe the development underway of a project called Voices from Central State. Designed to be a "memory archive/forum," it will serve as an online platform for people with a range of connections to Central State to share stories and photos as well as engage in discussion.

Copyright 2021

|